Thank you. [Applause]

Alright thanks.

So, I routinely fail my eye exams so I have my paper here and it will just be a test how well I know my slides.

So I am kinda making that transition to the chronic side of things.

And, you know, I'm going to start with talking about opioids, not 'cause that's where I want to start, but because that's what has been consuming us, I think, in recent history.

I'm a general internist and a primary care doctor.

And, you know, this is my background slide; this is the place of opioids in primary care.

You know, like, the whole world is sort of revolving around opioids.

Especially when we're talking about pain.

We're talking about addiction.

We're talking about mental health.

Everyone is talking about opioids all the time.

Umm... and so, it didn't have to be this way, but this is the way it is, and this is the way it was when I started to practice.

So, you know, my research has also sort of circled around opioids for better or worse.

Umm

This is my other background slide.

This is the evidence base for long term opioid prescribing as it stood when we started doing this, you know.

This did not-- this did not come down to us as results of multiple randomized, controlled trials showing us that this was an effective way to manage chronic pain, but indeed, you know, primary care was kind of delivered this message that

this is a moral obligation, we have an ethical duty to treat pain, and the effectiveness of this particular strategy was sort of assumed in these messaging-- in the messaging we received.

And just to provide an example of that, this is the first VA/DOD opioid prescribing guideline; a little section from this.

Released in 2003, incidentally the year that I was chief resident at the Minneapolis VA and trying to learn some stuff about pain so I can teach my fellow trainees about how to do it better,

and as you can see here, the recommendation is that opioid therapy is indicated for moderate or severe pain that has failed other interventions.

So if anything else doesn't work, opioids are indicated.

And consider the ethical imperative to relieve pain.

And I don't wanna pick on the drafters of this document, because it's just one of many, but this was the message we were all getting about this is good quality care.

And so sometimes people say to me, how can primary care have done this, and created this mess, and prescribed all these opioids?

Well, we were following guidelines and considering the ethical imperative to treat pain.

And, so, you know.

This is the 2017 guidelines which are a complete 180.

The first statement is "we recommend against initiation of long term opioid therapy for chronic pain."

And, you'll notice in the red box I've just, sort of, highlighted the evidence they cited for that,

primarily, the "rapidly growing understanding of the significant harm of long-term opioid therapy,"

but note still there are no studies evaluating the effectiveness of long-term opioid therapy.

So that did not stop the guideline drafters, from making a strong recommendation, but, you know, that's kind of been consistent with how we do it around opioids;

we have strong opinions and strong recommendations and simply not enough evidence.

Just another example of one of many systematic reviews that have found essentially the same thing, that we just don't have long-term effectiveness data

for this practice that has become so amazingly commonplace that opioid therapy is pretty much the most commonly prescribed treatment for chronic pain these days.

So, I'm gonna tell you a little bit about a trial that I recently completed that some of you know about.

I presented this at the Society of General Internal Medicine meeting in the end of April and no, the paper is not done, it does not impress, so I'm not going to tell you a whole lot.

I will only tell you a subset of the things that I have already publicly presented, but...

I wanted to at least give this to you as a... as a.. as a teaser any way.

So the strategies for prescribing analgesics comparative effectiveness trial was designed to compare benefits and harms of opioid therapy vs. non-opioid medication therapy over 12 months among patients with chronic back and osteoarthritis pain.

Why those two conditions?

Because those are the most common conditions for which long term opioid therapy is prescribed in VA and possibly outside of VA as well.

We chose non-opioid medication therapy as the comparator for opioids because that's-- I thought-- the most practical, common alternative in primary care.

Often what we're doing is deciding whether or not to start opioids or just to keep prescribing other stuff.

Although, there are many other pain treatment alternatives, they're not always as available or directly comparable.

So, we enrolled 240 veterans with chronic back or arthritis pain.

We randomized them in even numbers to opioids or non-opioids.

We followed them for 12 months and assessed their function, their pain, side effects, and many other things.

Our inclusion criteria were fairly straight forward.

They had to have at least moderate to severe chronic pain.

We require that this be the primary pain problem and not the only pain problem, and most these folks had a lot of other problems.

And we excluded people who had absolute contraindications to opioid therapy, so active substance use disorder, cognitive impairment psychosis, current long term chronic opioid therapy.

We did not exclude people with depression, PTSD, and those kinds of things, if they were getting some kind of treatment and weren't actively in crisis or suicidal.

So we randomized them to either opioid therapy or non-opioid therapy.

I should say that what partially makes this presentation, and this study, relevant to this audience is that we embedded this trial within a collaborative care model.

So all the participants in this study got individualize medical-- medication management within their assigned arm.

So the thing that differed between the arms was simply the menu of drugs that they had to choose from, but there was a pharmacist care manager who did the actual treatment for all patients.

They all got follow up visits monthly, and then every one to three months, mostly by telephone, they got treatment to target pain and individual functional goals that were established with that pharmacist at the first visit.

And this really use this telecare collaborative pain management model that I'll just briefly mention.

So this was a study led by Kurt Kroenke, funded by VA, published in JAMA a couple years that tested this telecare collaborative management of chronic pain and primary care.

Primarily -- the key components really symptom monitoring with the PEG, the PHQ-2 for depression, the GAD-2 for anxiety, and then medication optimization.

That's really the same approach that I used in this trial of opioid therapy vs. non-opioid therapy.

And in this trial by Kurt Kroenke, it was an effective intervention with twice as many people responding, 52% who received the intervention vs. 27% in usual care.

So, back to the current study.

All medications in both arms were on the VA formulary.

It changed a little over time and as a pragmatic trial, therefore, there were some changes in what was available.

Each arm had three medications steps.

In general, patients received treatments in each step before moving to the next one.

We limited the opioid daily dose to a hundred morphine equivalent milligrams a day.

And I'll say that, the ground moved so rapidly under the study as we conducted it, that, you know, we were just kind of reeling to keep up with the changes in people's perspectives.

Initially the plan was 200 morphine equivalent milligrams per day and I think we got a little reviewer blow back for that.

That why would you limit that?

But it didn't seem safe not to.

We've lowered it to 100 and we kinda had a soft halt at 60, where if people were not responding, we would really stop and reevaluate as opposed to going up, so not too many people hit the hundred mark.

So these are the drugs we used, and the opioid arm is on the left, the non-opioid arm is on the right.

The first medication at the top with the asterisk on both sides is the preferred initial medication unless we had some reason to start something else first.

So it was morphine IR in the opioid arm, and acetaminophen in the non-opioid arm.

People always ask me about this, because some of these drugs aren't totally evidence-based for chronic pain, but this is how it goes in primary care.

We didn't have a super high bar, but drugs that were used for chronic pain that had at least some evidence of efficacy somewhere, we included in the non-opioid arm.

You'll also notice on the bottom right hand there that tramadol is in the non-opioid arm.

Why? Again, the world changed between 2010 and 2017.

A lot.

Just running briefly through this.

We randomized 240.

All but one received the intervention at 12 months.

All but three in each arm gave us 12 month patient reported outcomes so, we had really excellent follow-up, and we included all but one in each arm in the analysis.

And this is the bottom line.

I'm just giving you the responder analysis, but the main differences tells exactly the same story.

BPI interference, the Brief Pain Interference scale, which is a measure of pain related functional impairment, there was no difference between the arms on that.

About 60% of patients in both arms had a, what we defined as a clinically significant improvement of 30% from baseline to 12 months.

And then BPI severity, our measure of pain intensity.

Umm...

Here the non-opioid arm was superior to the opioid arm, so 41% in the opioid arm had a significant improvement and 54% in the non-opioid arm, and that was statistically significant no matter how you cut it.

I wanted to show this to you.

This is the care management side of things.

You can see we actually did a really good job of giving equal attention to both arms so, on average, 2.8 in-person visits with a pharmacist over a year, six phone visits with a pharmacist over a year, and a grand total of almost 4 hours.

So our summary, opioid therapy was not superior to non-opioid medication therapy, and indeed there was a small significant difference favoring non opioids in pain intensity.

I didn't show you harms, but opioid therapy caused significantly more adverse symptoms.

And, umm...

So in addition to supporting the CDC guidelines that opioids are not preferred, I think it's worth, especially for this audience, pointing it out that we actually had good response rates in both arms.

Right, so...

I attribute that largely to the telecare intervention.

You know, these folks had treat-to-target pain management, which is not normally how we do pharmaceutical therapy for chronic pain.

And if things didn't work, we changed it, in both arms.

So I think that's why a lot of our people did pretty well, even if the individual medications prescribed maybe weren't fantastic.

So, what next? Moving towards the future.

Clearly we have a project in terms of de-implementing ineffective and inappropriate opioid therapy.

There is a lot of that out there.

Umm...

And... the other project really is implementing effective pain therapy.

So, many other interventions have better evidence than opioids do and many of these are pretty seriously underused.

I'll -- just to give you a real brief summary from a VA process that is actually ongoing

VA sponsored a state-of-the-art conference in the past year on non-pharmacological approaches to chronic musculoskeletal pain.

This was actually prompted by the White House, the former President's summit on the prescription opioid crisis and VA at that time committed to focusing on non-opioid therapy alternatives.

So this conference came out of that initiative, and the goal is really to get a group of experts together to look at existing evidence and gaps related to non-pharmacologic approaches for chronic musculoskeletal pain.

We divided that into four categories: psychological and behavioral therapies exercise and movement therapies, manual therapies, and then models for care delivery, most relevant to today.

The goal is to really identify approaches that the VA should consider implementing more broadly.

As well as identifying our research agenda for those approaches that maybe needed more work.

This is one slide summarizing, really, conclusions of the groups about the psychological/behavioral exercise movement and manual therapies categories.

These are the therapies that the conference concluded were ready for implementation on some level in VA, at least basic efficacy evidence being present for these therapies.

The research gaps really related to those same therapies and all the surrounding issues; delivery approaches, dose of therapy, strategies for improving adherence,

engaging patients, maintaining benefits, combining and sequencing therapies, all those kinds of things.

And I'm sure many in the room are not surprised about this.

I mentioned that the fourth category of approaches was this models for pain care delivery.

For this one,...

the group, we did not identify any existing systematic reviews on this topic, which was kinda interesting.

Really for all the other therapy approaches, there was a lot of systematic reviews to pull from.

So what we did was requested an evidence br- brief from the VA Evidence[-based] Synthesis Program and ask them to look at studies

that evaluated models using system based mechanisms to increase the uptake and organization of multimodal in pain care broadly defined.

We looked for interventions that were integrated with primary care, at least primary care adjacent, and specifically not multidisciplinary pain rehab programs done in specialties settings.

And this is just a summary slide from that evidence report, which I believe is available out there online.

The review found eleven articles describing ten different studies.

Umm...

They were mostly randomized, controlled trials of fair to good quality.

They rated 3 of the 10 as poor.

Most of them had 12 month follow-up, in contrast I think often to our pharmaceuticals studies.

Most use the usual care control and most enroll patients who had moderate to severe pain at baseline.

These studies described nine diverse models.

And the puzzle pieces, there are the four, kind of, categories of features that were common to these nine different models.

So, not surprising to anyone to hear that, common features were decision support, care coordination resources, efforts to increase patient knowledge and activation, and then increasing access to multi-modal care.

The review concluded that the best evidence existed for five models, four of which were described in good quality VA trials that combine decision support with case management.

And I think Steve Dobscha is going to talk a little bit more about some of these.

They were the ESCAPE, SEACAP, SCAMP, and SCOPE trials.

And the SCOPE trial is one I already mentioned that did the telecare collaborative management.

They also included the STarT Back trial as one of the study models for which evidence was best.

For these models, they all found a clinically relevant improvement in pain intensity and function.

And the conclusion of the report was really that VA should consider implementation of these models

in a multi-site manner and examine factors associated with successful implementation and effectiveness and practice at the same time.

So I am going to let our additional speakers talk more about challenges.

But this is a key challenge, I think, to moving forward, improving care, and that is that now opioids are basically a black hole for primary care energy, time, and honestly, good will.

You know, I think a lot of people just don't want to hear about pain because they are just sick of dealing with opioids.

And that is a real challenge that as we're doing this, we need to remember opioids are a drain.

What's exciting about treating chronic pain in primary care?

How can it feel good again, you know?

Does anyone ever have success?

Or feel like they did something for a patient and the patient got better.

We do need to-- we need to refind the joy here and escape our black hole.

And then I think this is just meant to represent the obvious structural issues, you know.

Usually it's just one little jump over a hurdle to get access to medication, but, you know, I was trying to get chiropractic treatment for a patient of mine who has low grade chronic back pain, who has an acute flare and that's what looks like, you know.

This huge Olympic hurdles course to try to figure out how you could get something pretty simple done in maybe a few sessions for the occasional patient who needs it.

So, meanwhile, she'd already had three opioid prescriptions, two benzo prescriptions, and two courses of prednisone from the ER.

So, you know, this is a challenge we will continue to face, and I'll let the rest of the speakers talk a little bit more about that.

Thank You.

For more infomation >> Tweakd Above the Clouds SelfCleansing Hair Treatment - Duration: 17:48.

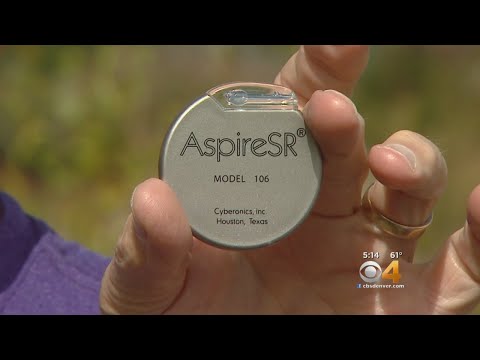

For more infomation >> Tweakd Above the Clouds SelfCleansing Hair Treatment - Duration: 17:48.  For more infomation >> Seizure Sufferer Describes Life-Changing Treatment - Duration: 2:19.

For more infomation >> Seizure Sufferer Describes Life-Changing Treatment - Duration: 2:19.  For more infomation >> Treatment hub opens in St. Albans - Duration: 1:38.

For more infomation >> Treatment hub opens in St. Albans - Duration: 1:38.  For more infomation >> Endodontic Treatment/Root Canal Treatment/RCT on my own tooth. Dentist treating his own tooth. - Duration: 30:18.

For more infomation >> Endodontic Treatment/Root Canal Treatment/RCT on my own tooth. Dentist treating his own tooth. - Duration: 30:18.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét